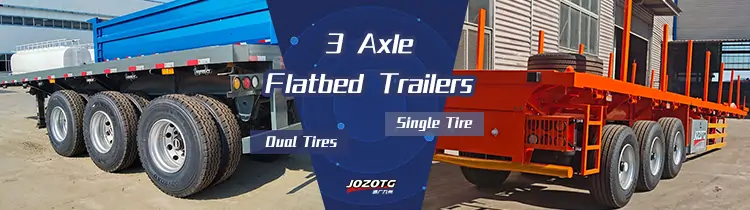

Across sub-Saharan Africa the verdict is almost unanimous: when a flatbed semi-trailer leaves the assembly line it carries dual tyres on every axle end. From the oil-palm plantations of Ghana to the copper belt of Zambia, the 8.25×22.5 or 12.00×20 dual assembly is still the default specification written into fleet tenders, bank lease contracts and even insurance policies. The reasons are historic as much as technical—spare rims, tubes and 10-hole stud patterns can be bought in every roadside village, and a driver who blows the outer tyre on a rough laterite track can limp 200 km to the nearest depot on the inner wheel. Yet the tyre landscape is no longer monolithic. A small but growing cadre of bulk-cement, bitumen and container feeders now specify the 385/65×22.5 “super-single” in order to pull an extra half-tonne of payload, cut diesel bills and present a more modern brand image to international clients. The purpose of this paper is to weigh the engineering and commercial realities behind each configuration so that African and Middle-Eastern operators can decide when the single-tyre revolution is worth the risk—and when it is merely marketing gloss.

The single-tyre value case: payload, fuel and the Saudi frontier

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where 385/65 R 22.5 super-singles arrived with Euro-6 tractor imports, the calculus is different. A single wide-base tyre eliminates 80 kg of unsprung mass per axle end, allowing a flatbed to legally scale 600 kg more payload on a 12-axle modular combination—critical for hauling 55 t of polypropylene pellets from Jubail to Riyadh in one night. Rolling-resistance tests conducted by Saudi Aramco show a 4.2 % drop in fuel consumption, worth USD 2 300 per annum on a 120 000 km route at USD 0.40 per litre. The Achilles heel is vulnerability: when the only tyre on the hub bursts, the axle drops instantly and the trailer becomes immobile on 50 °C asphalt, waiting for a specialised service truck that may be 400 km away in Dammam. Procurement cost is also higher—USD 520 for a premium 385 versus USD 320 for two 315/80 duals—but the operator saves one casing over the life cycle, and the lower heat build-up extends tread life by 8 %. Crucially, the Kingdom’s roadside infrastructure is evolving: Al-Futtaim MAN now stocks 385 mm casings in Riyadh, Jeddah and Dammam, and mobile repair vans carry wide-base beads. For African adopters the lesson is clear—super-singles make economic sense only if the corridor is paved, the rescue window is under six hours, and the fleet can negotiate a parts-consignment contract with the supplier. Where those conditions are met, the single tyre delivers higher productivity and lower total cost; where they are not, the African dual remains king of the road.

Dual-tyre dominance: why 90 % of African decks still run twins

The dual assembly’s foremost advantage is redundancy: lose one casing and the partner tyre will still carry 4.5 t at 50 km h-1, enough to reach the next bush workshop where a used 12 R 22.5 can be fitted for USD 80. Fleet data collected by our Nairobi technical centre show that 73 % of blow-outs on tandem axle groups occur on the outer wheel, allowing the driver to continue without even unloading the deck. This built-in safety margin is priceless on the Moyale–Isiolo corridor where roadside assistance can be 36 hours away. Capital cost is also lower: a 22 × 9.00 steel dual rim retails for USD 95 in Lagos, whereas a 22.5 × 13.00 wide-base single rim is USD 185 plus 8 % import duty, and the 385 mm wide-base tyre itself carries a 35 % premium over the 315/80 dual equivalent. Finally, the African support ecosystem is overwhelmingly dual-tyre centric—every village tyre cage stocks 10-hole rims, split-ring tools and tubes, while mechanics have been resealing them since apprenticeship. The downside is operational: duals must be replaced in matched pairs to avoid diameter-induced scrub, and the extra tread mass increases rolling resistance by 2.3 %, adding roughly 250 L of diesel per 100 000 km on a 30 t GCM combination.